The best aperture taking into account both depth of field The smallest aperture give the best results. In this case one has a paradox, since no longer will using

At this point the effects of diffraction can start toīlur the image more than the effects of defocus due to limited depth Avoid apertures smaller than f/8 orĪrticle is for people shooting film cameras that stop down to f/32 Just use a tripod and choose the smallest aperture you have if you You are a beginner or just shooting a 35mm or digital camera then thisĪrticle addresses issues which won't bother you at reasonable apertures.

#BIG APERTURE VS SMALL APERTURE HOW TO#

Read on and I'll show you how to calculate your own.īuy from Adorama, Amazon, Ritz, B&H, Calumet and J&R.Īrticle is written for the virtuoso large format Nikon, Canon, Leica, Pentax and most 35mm cameras:ĭon't have depth-of-field scales on your zoom or digital lens? You're screwed, sorry. Once you've read the aperture your camera suggests, here's how to convert it into the sharpest aperture: When I'm shooting, I use my thumbnails to mark each distance, making it easy to rotate the focus ring to midway between the two distances and read the f/stop. You don't have to be exact f/8 is more than close enough. You've now also focused exactly as you should for the best overall sharpness, whoo hoo! enlarge.Īnd you'll read f/8: both 10 feet and ∞ are sitting above f/8 on the depth-of-field scale. Turn the focus ring until each distance is equally far from the center index, and you'll see that each distance lies next to the same aperture number on different sides of the scale.Īs an example, let's suppose we want everything from 10 feet (3 meters) to infinity in perfect focus.ĭepth-of-Field scale, Leica 40mm f/2. Focus on the nearest thing, and note its distance on the scale. To use your depth of field scales, focus on the farthest thing you want sharp. You use your existing depth-of-field scales, and simply use the apertures shown on my chart instead of those read on your lens. It's very complex if you want to read this whole thing, but for 99% of you, here's all you do. What do we do when we do need depth of field? My lens reviews give the best apertures for each lens, but it is almost always f/8 if you need no depth of field. If you're shooting flat subjects, the sharpest aperture is usually f/8. The very best aperture is someplace between these two, and I'm going to show you how to find it exactly. If you stop down more you get sharper results, but if you stop down too far, diffraction gives you softer results, just like squinting your eyes. They do not calculate the aperture which will give you the sharpest photo, just the bare minimum.ĭepth-of-field charts and scales came from an era where film was very slow and we always needed the widest aperture possible. They calculate the largest aperture that will give barely passable sharpness. If you read all of it, I'll probably lose you, but I'll summarize it all right here.ĭepth-of-field calculations are flawed. I originally wrote this article back in 1999. Ultimately, it’s all about keeping that detail sharp throughout and not just whether or not it’s in focus.Home Donate New Search Gallery How-To Books Links Workshops About Contact This is why many macro and landscape photographers often resort to focus stacking – even if stopping down to f/22 or f/32 would give them the depth of field they need in a single shot. It can be tough sometimes finding that balance between giving you enough depth of field and an acceptable level of sharpness. I mean, what other 800mm prime lens can be bought from a reputable brand for less than $1,000? And having a fixed aperture also means less engineering and also helps to keep the costs down for the consumer. But with the potential diffraction issues, there’s really no reason for a lens that already has such a small aperture to really let you go any smaller. Having a maximum aperture of f/11 means they can make the lenses small (and inexpensive). But as camera resolutions have increased to 36MP, 45MP and even higher resolutions, diffraction has become a lot more noticeable and a bigger problem for photographers.ĭiffraction potentially explains why Canon’s recently released Canon RF 600mm f/11 IS STM and Canon RF 800mm f/11 IS STM lenses have a fixed f/11 aperture. It was still there and noticeable if you really pixel peeped, but you could still often get acceptable sharpness (although “acceptable” is subjective) at beyond f/11. When digital cameras were still in the 16-megapixel or lower resolution stage, diffraction wasn’t that big of an issue a lot of the time.

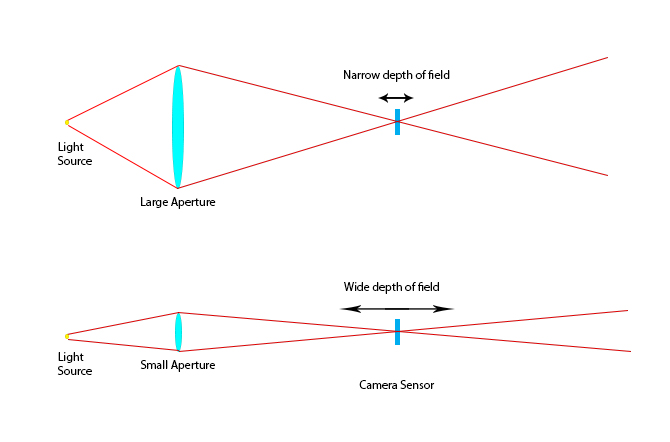

You might have noticed that you get to a certain point with your lenses that when you keep stopping down, your images get softer again.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)